The Odyssey of Black Studies in Public Broadcasting

The Formative Years

Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which comes from the teaching of biography and history.

- Carter G. Woodson, The Mis-Education of the Negro

During the transformative closing years of the 1960s, when the Black Power Movement arose, American colleges and universities became battlegrounds for Black education and cultural history. Influenced by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panthers, and other Black radical organizations, many Black students began organizing Black Student Unions to demand equity in the classroom and justice by the university system.1 These unions became key spaces for the development of Black radical politics aimed at student autonomy and affirmation, and as indicated in the Say Brother episode “Black Power on University Campuses,” the places where whispers of protests and striking would begin.

San Francisco State University was the focal point for the beginning of the Black Studies movement. Impelled by the university administration’s mistreatment and racism from the white student body, the university’s Black Student Union—with assistance from other student organizations such as the Third World Liberation Front—began a five-month strike on campus to demand equity.2 Demanding the admission of more Black students and the “creation of independent-ethnic studies programs,” the BSU won, and San Francisco State became the first university in the nation to have a Black Studies program under the direction of sociologist Nathan Hare.3 Soon, Black Studies programs would begin to rise in number across the nation at colleges such as Temple University, UCLA, and Harvard University. According to Black Journal producer and host Tony Brown, "The rebellion ushered in Black Consciousness…. Values had to be defined, and an institution created to define those values. It was called Black Studies.”

Public broadcasting’s coverage of the founding years of Black Studies focused both on the inciting incidents that led to the founding of the programs and the programs themselves, examining the teaching pillars of Black Studies and its impact on the students that these programs served. While the coverage of Black Studies in its infancy by local news affiliates is scarce, radio and news programs run by Black journalists covered Black Studies extensively and included one-on-one interviews with many leaders and educators.

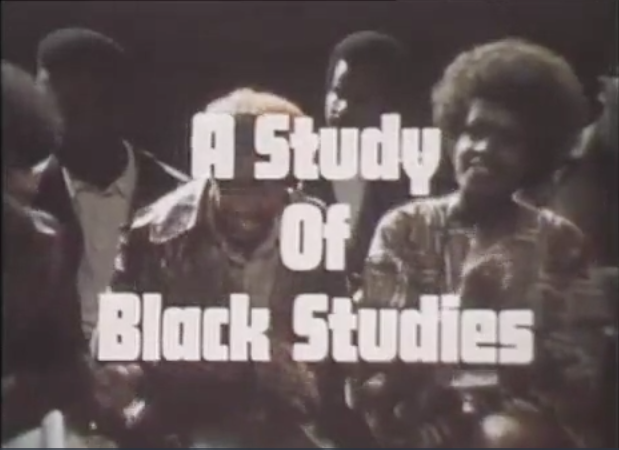

National Educational Television’s Black Journal crafted a two-part program exploring Black Studies itself, investigating its politics, educational goals, leadership, and student responses. Titled “Take Back Your Mind, Part 1” and “Take Back Your Mind, Part 2” and airing in 1971, just a mere two years after these programs began, Black Journal executive producer Tony Brown conducted an investigative report on Black Studies programs particularly in California, where much of the action related to the founding of Black Studies took place. Brown showcased the intent of Black Studies: to provide an institution that centers Black consciousness and gives voice to the history and culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora as a whole. Brown took viewers within Black Studies programs at the University of California, Nairobi College, California Polytechnic State University, Federal City College (now The University of the District of Columbia), and Malcolm X Liberation University. Speaking to a wide array of people, from the program’s first students who discuss the importance of these programs, to program founders and professors who designed the curriculums, this two-part survey attempted to define the need for Black Studies and its indelible effect on higher education during its infancy.

In July 1969, KUT, a public radio station based at the University of Texas at Austin, broadcast a two-part program in which their university’s ethnic studies program director, Dr. Henry Bullock—who was also the school’s first Black professor appointed to the faculty of arts and sciences—detailed the advent of Black Studies at the university.4 The program left a significant mark, as the following year, KUT Radio launched In Black America, a now-syndicated radio show covering varying aspects of the African American experience, from culture to politics and more.

As national coverage of Black Studies increased, so too did criticism of the programs themselves, with many questioning the purpose of Black Studies and its legitimacy in higher education. For a 1969 episode of Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr. titled “Afro-American Studies,” Black scholar C. Eric Lincoln and David Brudnoy, a white scholar who taught Black history, were invited to discuss Black Studies and encourage Americans to support its presence in colleges. Lincoln was a professor at New York City’s Union Theological Seminary and Brudnoy was finishing his doctorate at Brandeis University, which was in the process of starting its own African American studies program. Buckley served as the voice of “concern” for American conservatives who believed “that many students who are asking for Black Studies programs, administered by Black students and faculty, are asking for them as a way of relieving themselves of the normal rigors of academic life.” Despite many objections to Black students wanting to be taught Black courses by Black faculty, Lincoln made it clear that “the reason why we are now confronting this issue of Black Studies, is precisely because this aspect of human experience has been ignored. Our academic curricula have been constructed for three hundred years as if no Black people ever lived.” Lincoln, like many of his colleagues, aimed to show that when it came to African Americans and the Diaspora, “that they did live, and what they did and they said and what they wrote and the art they produced was significant. We are simply now saying that they are a relevant part of the human experience.”

After the first five years of Black Studies rising across the nation, coverage of the programs began to wane with much now falling to local Black broadcasters in programming such as Black Journal, Say Brother, and In Black America. While the number of Black Studies programs continued to rise during the 1970s, reports on the programs switched from focusing on their founding and need, to examining the systemic barriers and structural issues these programs faced from their respective institutions.

|