The Odyssey of Black Studies in Public Broadcasting

Black Students and Faculty in Higher Education

On October 11, 1990, Dr. Carla Peterson, a Professor of African American Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Maryland, spoke at a forum on the state of Black Studies in the nation. During her opening remarks, Peterson quoted famed Black feminist scholar bell hooks who examined the margins of society as “a space of radical openness and possibility.” Peterson reflected on this quote and its relation to her own position as a Black woman in higher education, where she too felt she existed on the margins of her chosen field.

Black Studies was created with the intent to serve Black students who existed on the margins of the colleges and universities they attended, and aimed to center their history and culture in their educational pursuits. As Black Studies programs expanded across the nation, Black faculty and administrators also grew in numbers, leading to mass efforts to improve the quality of cultural education that Black students received. Public broadcasting documented this push for change and equity at colleges and universities by speaking directly with the faculty and department heads of varying Black Studies programs.

Afro Studies: Why So Many Barriers?

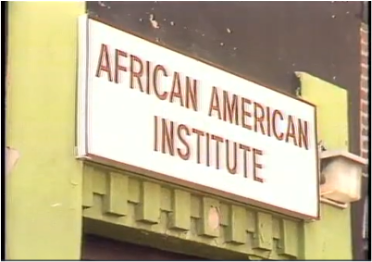

In May 1979, the WGBH program Say Brother covered the Black Studies programs at colleges within the Boston area: Harvard University, Boston University, and Northeastern University. Journalist George Rivera went inside the programs to “establish a case delineating some of the perpetual, institutional obstacles placed on Afro Studies programs from their inception” and with the hope to “present information that would spur continued support for the expansion and enrichment of university-subsidized, Third World heritage programs.” When speaking with Black faculty at Northeastern University, Rivera noted that the school itself had an “African American Institute” that had preceded the school’s Black Studies program, where community members and students could take coursework on Black culture free of charge. Despite this access and support, Black students at Northeastern who attended these classes could not receive actual college credit for them. Dean Gregory Hicks revealed to Rivera that a group of twenty-five minority students—backed by the Ford Foundation to diversify the student body—had demanded racial equity from the university administration in 1968 and saw their plans for the institute realized after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. In 1973, the Department of African American Studies was founded, only five years after Northeastern’s African American Institute was established. Dr. Virgil Wood, the institute’s director, described his responsibility to “plan and implement a range of academic and support programs, both cultural and social for Black students at Northeastern.” Wood stated that many Black students at universities were subjected to a “revolving door” where they were recruited, but not retained through graduation, and he believed that his institute could bridge the retention gap Black students faced. Dr. Holly Carter, who served as the chairwoman of Northeastern’s African American Studies program during its early years, spoke for the importance of the institute and the department working as a unit in order to service the marginalized Black students.

|

The episode included a profile of Boston University’s Afro-American Studies program, which only served graduate students and arose out of peaceful negotiations with the university administration. The segment featured Dr. Adelaide C. Gulliver, the program’s director who described how student objections to the way that Black history and culture were being presented in classrooms had led to her and other faculty members’ involvement. Because Black students were dealing with more pressing issues concerning their lives at Boston University, as well as because the university had a pre-existing African Studies graduate program, the graduate school crafted a plan to implement an Afro-American Studies program, rather than a full department.

Traveling from Boston University to Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Say Brother episode spent its third act exploring the most politically charged of the three Black Studies programs. Students and faculty at Harvard were in the midst of protesting the institution for its failed promises to its Black population. Engaging in a day of protest called “Afro Day,” the students and faculty challenged the university administration’s interference in funding the Afro Studies program and offering its faculty tenure. The protesters’ speeches on campus emphasized the importance of teaching from a Black perspective, and how a lack of funding and continued obstruction of the Afro-American Studies department was an attack on the Black student body. Dr. Ewart Guinier, the chair of the Afro Studies department, stated that he believed progress had not been made because “Harvard professors from the nineteenth century unto the present have been discussing, talking about, investigating Black people from a Eurocentric perspective. Their conclusions have been that Black people have made no contributions to society at any time.” Guinier further stated that “Afro-American Studies look at the Black experience from a Black point of view, a Black perspective … and we understand that Blacks have been the redeeming factor in bringing the United States to at least voice progressive ideas and that Black people, such as Martin Luther King, are the ones that are able to provide a vision for all Americans.”

In Black America: Radio Coverage of Black Studies

University of Texas at Austin’s KUT program In Black America has covered the culture and timely conversations of Black Americans since 1970. Several episodes of the series have focused on Black Studies. In December 1985, host John L. Hanson Jr. spoke with Black faculty members in Black Studies programs and what they found their responsibilities and challenges to be as pillars of Black cultural education. Hanson sat down with two Black Studies professors at UT Austin, Dr. Reuben McDaniel and Dr. John Warfield, to explore their respective careers within the university system and how their jobs required them sometimes to go beyond the scope of what is normally expected of professors.

Dr. McDaniel spoke about initially not understanding why Black students frequently searched for community with Black faculty members, as students and faculty did not have much in common due to the significant age gap between them. Dr. McDaniel noted that as his tenure at UT Austin extended, he realized that there was a dual role of Black faculty members on campuses not just to be knowledgeable about their respective fields, but also to be experts on Blackness and assist Black students, which he described as a “critical role” due to the marginalization of Black life on campuses. Due to the significant lack of Black people with doctoral degrees at American colleges in the 1960s and an increase in the years since, Dr. McDaniel discussed how those coming through the cracks must take on a greater responsibility in order to ensure that Black Studies continue on campuses.

When speaking to Dr. Warfield, director of the African/Afro-American Studies and Research Center at UT Austin, Hanson noted that Black Studies programs served as some of the only spaces for dialogue on the current state of Black Americans in the nation. Dr. Warfield expounded on this point, arguing that Black Studies programs functioned as “rehabilitation, the need to restore the historical and cultural realities of Black people in the academic arena,” as well as “self-knowledge to bring Black history and culture to a relevant place in the lives of Black people, and hopefully America.”

In the 1997 episode, “Doctoral Study Is the Possible Dream for Black Students,” John L. Hanson Jr. spoke about attending historically Black college Florida A&M University’s annual conference on minority student retention from K-12 education to doctoral study. At the conference, Dr. Israel Tribble, president and CEO of the Florida Education Fund, explored ending gaps for doctoral program enrollment, stating that “reasonable people with reasonable intelligence get PhD degrees.” Comparing education to the idea that “if you walk, you can dance,” Tribble pushed forward the idea that special skills are not required to enter and complete a doctoral program, and that success in these programs can be easily taught. Due to the continued isolation of Black faculty on college campuses, Tribble believed that a rise in the numbers of Black doctoral students would work to increase Black representation in higher education, lessen the marginalization of Black students, and aid the fight for funding for Black Studies programs.